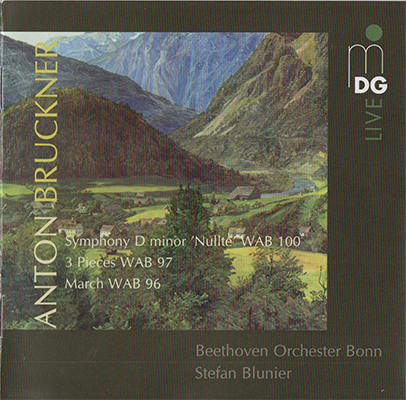

Beethoven Orchester Bonn, Stefan Blunier – Franz Schreker: Irrelohe, Opera In 3 Acts (2011) [SACD / MDG Live – 937 1687-6]

Title: Beethoven Orchester Bonn, Stefan Blunier – Franz Schreker: Irrelohe, Opera In 3 Acts (2011)

Genre: Classical

Format: MCH SACD ISO + Hi-Res FLAC

Franz Schreker (originally Schrecker, March 23, 1878 – March 21, 1934) was an Austrian composer, conductor, teacher and administrator. Primarily a composer of operas, his style is characterized by aesthetic plurality (a mixture of Romanticism, Naturalism, Symbolism, Impressionism, Expressionism and Neue Sachlichkeit), timbral experimentation, strategies of extended tonality and conception of total music theatre into the narrative of 20th-century music. The opera was first performed on 27 March 1924 at the Stadttheater Köln, conducted by Otto Klemperer. Productions in a further seven cities followed (including Stuttgart, Frankfurt and Leipzig), but critical response was mixed and, together with changing audience tastes and the complexity of the score, the work failed to maintain its place in the repertoire. The first production in modern times was at the Bielefeld Opera in 1985. The work was also staged at the Vienna Volksoper in 2004 and at the Bonn Opera in 2010. Wikipedia

The operas of Franz Schreker (1874-1934), composed during the early years of the 20th century and once as popular as those of Richard Strauss, quickly disappeared from the musical scene. This was not only due to the composer’s death in 1934, but also the rise of National Socialism in Germany. The latter precipitated the composer’s dismissal from his teaching post at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin in 1932, and probably also contributed Schrecker’s early demise from a stroke. Thanks to his Jewish heritage, Schreker’s compositions were characterised as ‘Entartete Musik’ (degenerate music) by the Nazis and his music like that of his near contemporaries, Zemlinsky, and Korngold and many other non -Aryan composers, were banned. In recent years, however, there has been a welcome if somewhat fitful re-kindling of interest in Schreker’s music. A number of the composer’s nine operas have been recorded and also received stagings, predominantly but not exclusively in Europe. These include ‘Der ferne Klang’ (1910), ‘Die Gezeichneten (1915), ‘Der Schatzgräber (1918) and ‘Irrelohe’ – premiered in 1924 in Cologne and conducted by Otto Klemperer. The music of the earlier operas mentioned above is characterised by lush harmonies and opulent orchestration – a heady mix of Puccini, Richard Strauss and the impressionism of Debussy. In ‘Irrelohe’ Schreker moves to a much more chromatic and contrapuntal style spiced with a little dissonance, and this is just one of the reasons why the opera was not well received by audiences and critics in 1924. Falling between two stools, the music was too decadent for progressives and too harmonically adventurous for conservatives. The orchestral forces involved are exceptionally lavish. In addition to a large compliment of strings, wind and brass there is a percussion section that includes two sets of timpani, three anvils, glockenspiel and xylophone. An on-stage orchestra consisting of two piccolos, two clarinets, six horns, three trumpets, percussion, bells and organ completes the line-up. The complex Gothic plot involving rape, madness and murder is typical of Schrecker’s febrile imagination and, for those attuned to late-romantic and expressionist opera, the work’s blend of blatant eroticism and verismo excess make for an intoxicating aural experience. Schreker is a master at creating atmosphere and much of the finest music in the opera is to be found in the many long orchestral passages in each of the three acts. The glittering and iridescent orchestral colours constantly beguile the ear while the ‘sehnsucht’ of the ecstatic vocal lines in the Act 2 scene between Eva and Heinrich echo Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. This MDG recording stems from recent live performances given at Theater Bonn (November 2-3,5,7, 2010) where the current Generalintendant Klaus Wiese seems to be spearheading a fresh revival of Schrecker’s stage works – a new production of ‘Der ferne Klang’ is scheduled for the 2011/12 Season. The performance by the Bonn company is very fine indeed. The opera’s two main protagonists are thrillingly sung by Ingeborg Greiner (Eva) and Roman Sadnik (Heinrich) who cope valiantly with their demanding roles, and Mark Rosenthal makes a most effective Christobald. The many lesser roles are also well sung. The playing of the Beethoven Orchestra Bonn under Stefan Blunier is magnificently full blooded and finely etched. Blumier relishes the score’s sumptuous textures yet, in spite of Schrecker’s heavy orchestration, he manages to keep instrumental lines clear. Two small caveats to this set must be mentioned. First the 75-page booklet included with the discs contains a proselytising essay on the work by Janine Ortiz, biographies of the singers and an Act by Act synopsis of the story, but – and it is very big but – a libretto in German only. Unless you are a fluent German reader the action will often be difficult to follow thanks, not least, to the opera’s labyrinthine plot. Secondly, each of the opera’s three Acts is allotted a separate disc. This does obviate the problem of choosing a suitable break (the Sony two-disc CD set from 1995 was particularly unfortunate in that respect), but it does also have a cost implication – three full-price discs instead of two for an opera lasting 127’ 50”. The vivid MDG recording is slightly distanced, so the volume needs to be increased considerably for its fine qualities to become evident. Balances between voices and orchestra are excellent, and for those listening in multi-channel the surround speakers have been used to great effect for the off-stage brass, distant bells and chorus in the Act 3 cataclysmic immolation of Irrelohe castle. There is no applause or audience noise but the movement of singers on the stage is clearly defined with very few extraneous sounds being captured by the microphones. This is latest addition to the Schrecker discography will be welcomed by all admirers of the composer and can be confidently recommended.